In a “tax incidence” analysis, MIA student Jan Panhuysen asked if consumers really benefitted from a tax cut for women’s sanitary products.

When the German government decided to cut taxes on women’s sanitary products in late 2019, Hertie School student Jan Panhuysen had just been studying “tax incidence” in his Advanced Economics course. Panhuysen saw in the event a perfect test case for reassessing recent findings in economic research: while businesses typically pass on value-added tax increases to consumers, they often don’t lower prices when VAT is cut. Lowering taxes therefore might not affect consumers, but instead merely increase companies’ profits.

The first-year Master of International Affairs student, who worked in software development before coming to the Hertie School, decided to take a closer look at the tax break case that made headlines in Germany last year. Until 2019, sanitary products for women in Germany were still taxed at the standard value-added rate of 19%.

A group of women’s rights activists, in collaboration with NEON magazine and start-up einhorn, petitioned the German government to lower the tax. They succeeded: after a landmark vote in German parliament in November 2019, it was decided that the amount of tax on sanitary products would be cut from 19% for luxury goods to 7%, which is the rate for daily necessities, starting from January 1, 2020.

Germany’s two largest drugstore retailers by sales launched ad campaigns promising they would pass the cuts on to consumers – even before the tax cut took place. Jan Panhuysen wanted to find out if they would stick to their promise. Professor of Economics Christian Traxler encouraged him to pursue the project outside the course, which concluded just before the tax cut took place.

“Tax incidence is one of the topics we cover in Advanced Economics and through a real-life research project like this one, students are able to show how something that may sound quite technical is actually very relevant. Tax incidence questions pop up everywhere and are relevant for everyone,” Traxler said.

With the help of a web scraper – a software that extracts and collects data from websites – Panhuysen gathered specific data from the websites of leading drugstore retailers in Germany, such as selling price, units and producers, beginning in November 2019, to indicate whether the price for tampons – the product with the highest demand among consumers – actually dropped after the VAT decrease.

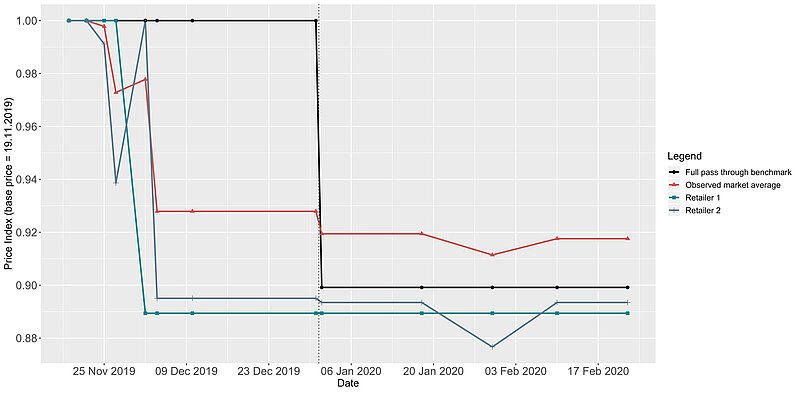

First, Panhuysen computed a benchmark price drop (the black line in the graph) that would take place if retail stores were to pass on the full tax cut to consumers – a drop to approximately 90% of the pre-reform price. A proxy for the market average between November and February, which is based on price data scraped from the web of the key (but not all) retailers, is shown in red. Panhuysen’s analysis revealed two main findings: First, the trend in market prices suggests consumers already saw a price drop in early December. This is in line with the two largest retailers’ ad campaign promises. Second, the average price after the reform on January 1, at around 92% of pre-reform levels, is quite close to that of the benchmark case. In fact, the two largest drugstore retailers (which rounded down their lowered prices) even held prices below the benchmark price drop (depicted by the black line).

The policy implications from the analysis are straightforward, Panhuysen said. The tax cut did achieve the desired objective: Prices of women’s sanitary products dropped and most retailers did not exploit the tax cut – at least in the short-run. In order to draw long-term conclusions, Panhuysen plans to continue collecting more data over the coming months.

Technical details and disclaimer:

The web-scraper used for this analysis was built in RScript. The script is given a certain list of websites that it is supposed to collect data from. This collection is then based on so called “nodes” such as “.rs-price”. These nodes vary from retailer to retailer, however, are usually the same all over the respective store. The nodes are assigned to a certain position on the website and are used to easily change, for example, prices in the background and to tell websites what to display on the web shop and to customers. By running the script, the web scraper then “reads” all information stated in those nodes and combines them into a unique dataset. When repeating the process, a new column with the respective prices on the date of running the script is added.

As a result, the database consists of a total of 88 products, of which 58 were sold at the two largest retail drugstores. As the data has not been subject to manipulation such as an industry weighting, it purely reflects the data scraped from the web.