The key to India’s digital transformation, the Aadhaar e-ID system acts as the glue which holds together India’s digital ecosystem. However, the implementation of such a large, encompassing programme in the world’s largest democracy has not been without its challenges and criticisms.

In 2010 India launched an ambitious electronic identity (e-ID) programme known as Aadhaar, or ‘foundation’ in Hindi. With its debut, India became the world’s largest democratic living laboratory for the testing and establishment of a functioning e-ID system. Based around the collection of biometrics and basic demographic information, the system has, to date, registered 1.25 billion Indian citizens. Aadhaar is particularly unique because it goes much further than simply providing identity: its numbers are directly linked to citizens bank accounts, allowing the government to automatically process welfare payments (known as Direct Benefits Transfers or DBT). This represents a great improvement in the distributive efficiency of India’s notoriously wasteful welfare system, which transfers nearly $60 billion a year.

However, the implementation of Aadhaar has not been without its controversies. The extent of its reach has been criticised, and others fear it will be used by the government or hackers for mass surveillance. Some experts have even challenged the World Bank estimates which claim the programme will save the country $11 billion a year. Controversy aside, electronic identity systems like Aadhaar are nonetheless a key foundational aspect for the future of digital governance. The UN Sustainability goals (SDG 16.9) even include the provision of a legal identity for all by 2030 as a target. Aadhaar represents a new, ambitions, and potentially highly beneficial technology, and it is thus important to explore the challenges and experiences with its implementation so far.

The Aadhaar Ecosystem and Services

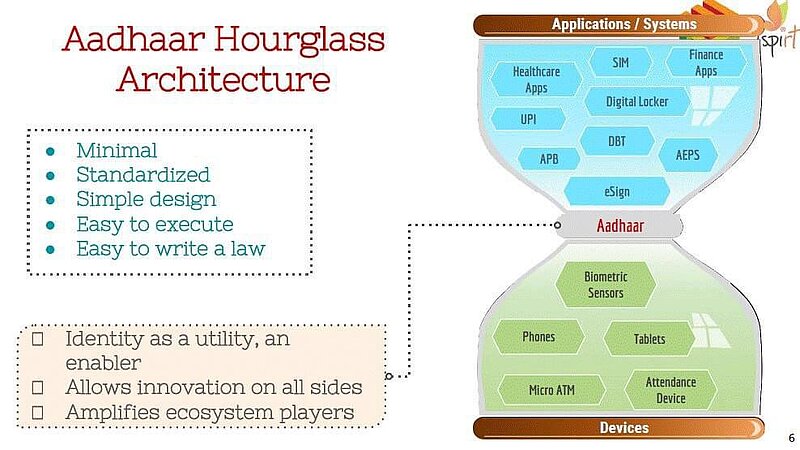

The key to India’s digital transformation, the Aadhaar system acts as the ‘glue’ holding together India’s digital ecosystem, which is comprised of both private and public organisations, start-ups, lobbying bodies, and civil society organisations. The ‘hourglass architecture’ (Figure 1) of Aadhaar provides linkages between the points of access at the bottom with the services built on top.

Aadhaar supports a particular set of open APIs known as the India Stack, which are used to develop its various digital service. Some of these services include:

- Payment services for bank transfers using only the Aadhaar number

- An Aadhaar payment bridge for government-to-citizen transfers

- A mobile one-time password (OTP) for authentication purposes

- An electronic Know Your Customer system (eKYC)

- DigiLocker, a download service for government issued documents

- Verified digital signatures

Using the Unique Identity Number (UID) of the Aadhaar system, Indian citizens can log in and make use of multiple government services, either biometrically or via the generation of an OTP sent to their phone. The Unique Identity Authority of India (UIDAI), keeps a record of all the places where each citizen has authenticated his or herself; and this data is kept on record for six months. Developing such an ambitious set of services has not been without its challenges in a country where digital illiteracy is common and the necessary hardware such as Point of Sales systems are not yet widespread. According to a state report from 2019, 6.7% of the population was still excluded from various services. As will described in the next section, Aadhaar has also been revealed to have some very significant weaknesses in its structure and governance model.

A Novel Model in Digital Technology Governance

Aadhaar’s development was facilitated by an informal Private Public Partnership (PPP) model which was the first of its kind in India. Primarily as a cost saving measure, former Chairman Nilekani formed the PPP model by recruiting the best talent from the private sector to work as volunteers. The incentive to volunteer was primarily due to the prestige of being associated with the national digital transformation programme.

As pointed out by some experts, this volunteer led open-source PPP model has come to define India’s technology governance. While much of the success of Aadhaar’s development can be assigned to the PPP model, this has also led to significant conflicts of interest. Individuals who worked on the Aadhaar project as volunteers now lead a number of private organisations which operate in the Aadhaar ecosystem and provide the digital services listed above. The lack of a formal and binding data protection bill and Data Protection Authority (DPA) unfortunately provides these private actors (for example, here and here) the leeway to process citizen data however they wish with impunity.

The Road Ahead

The implementation and controversies surrounding Aadhaar is to be expected, not least due to the wide gap in socio-economic inequality, large population and wide geographical area. However, at the same time, Aadhaar’s progress is important for its international significance— over a hundred countries, a majority of them in the developing world, have since rolled out similar programmes that provide some form of digital identification for their citizens. Aadhaar’s appeal lies in its minimal biometric data collection and in its avoidance of fragmented biometric databases and proprietary technologies that increase costs and reduce gains from digitisation. Aadhaar has also significantly brought down the cost of Know Your Customer, allowing the Indian government to significantly expand its banking and financial services to the poor and streamline its welfare payments through the use of direct transfers.

Aadhaar’s improved access, however, brings with it new threats to cyber security. Aadhaar requires a monitoring and learning system with a strong access control mechanism which can evolve as security threats present themselves. It is of course impossible to design a totally secure system, but, it is nevertheless vital that in the future the programme maintains a dual focus on strategic IT availability and digital learning for citizens (including data privacy training for officials) to ensure secure and increased access, availability and uptake of digital services.

Aadhaar can certainly become a successful strategic policy tool and model for social and financial inclusion and welfare. However, for this to happen, the national and global discourse must focus on how best to balance the gains from better digital governance with the individual’s right to privacy.

Figure 1 Source: iSPIRT