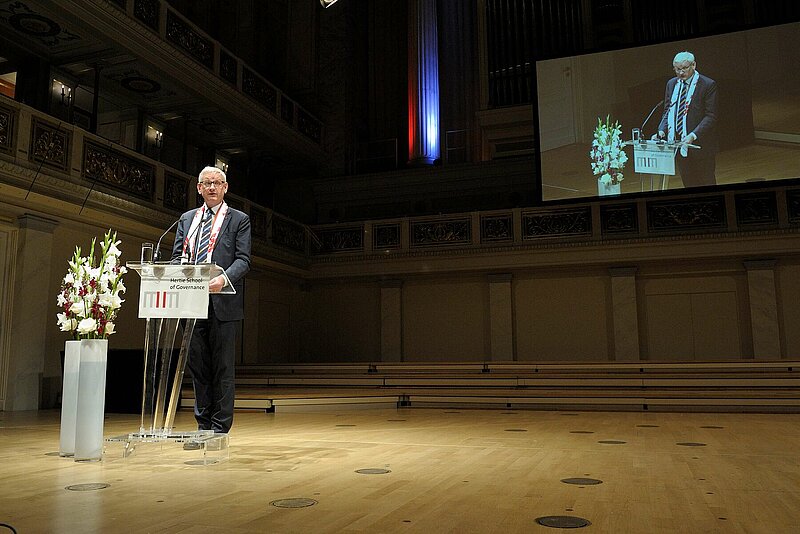

The following commencement speech was delivered by Carl Bildt on 8 June to the Class of 2018 at the Konzerthaus in Berlin. It has been edited slightly for the purposes of publication.

First.

It’s an honor to be invited to address you on this so important day for those of you now graduating from this prestigious institution.

Second.

It’s always a pleasure to come to Berlin. After years of dictatorships, destruction and division, Berlin is emerging as a vibrant European metropolis, generating thoughts that vibrates across Europe and attracting talent from near and afar.

Here, history is always present. Here, it is necessary to think about politics beyond the immediate issues of the day. Here, you can’t avoid the broader issues of our time.

In August of 1941 two gentlemen met on a battle cruiser off the coast of Newfoundland in Canada. The armies of Hitler were still sweeping victoriously over the plains of Russia and Ukraine.

But Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill still had the courage to set out their vision for the world after the victory that they at that stage could only hope for.

The Atlantic Charter was indeed a visionary document.

It spoke of a world of no territorial aggrandizement; no territorial changes made against the wishes of the people, self-determination; restoration of self-government to those deprived of it; reduction of trade restrictions; global cooperation to secure better economic and social conditions for all; freedom from fear and want; freedom of the seas; and abandonment of the use of force, as well as disarmament of aggressor nations.

And in the years that followed their and their allies victory this vision was gradually turned into reality.

The United Nations was set up, and adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The Bretton Woods institutions - IMF, the World Bank - saw the light of the day. The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, later evolving into the World Trade Organisation of today - was entered into.

And a determined effort was made to turn the enemies of yesterday into the allies of tomorrow, and to build networks and structures of alliances and integration, notably here in Europe, to secure peace, safeguard freedom and to foster open societies and open economies.

The results, when we now look back, were remarkable.

I was born in a world of 2.5 billion people, the overwhelming majority of which lived in extreme poverty.

And I vividly remember the expectations when I grew up. There were certainly fears of nuclear war, but there were also fears of a population explosion where more and more would be increasingly poor and increasingly desperate.

It didn’t turn out that way.

Today we are living in a world of 7.5 billion people, and a rapidly diminishing share of them lives in extreme poverty. The UN puts that figure at well below 10%.

Developments have been particularly pronounced during the somewhat more than a quarter of a century that has passed since the demise of the Soviet empire, the liberal economic reforms of India and the more pronounced opening up of the economic system of China.

This has of course gone hand in hand with profound developments in science and technology, and the spread of this knowledge throughout the world.

Not only have we seen hundreds after hundreds of millions of people lifted out of extreme poverty, and the emergence of a new global middle class from Shanghai to Sao Pablo, but we have also seen remarkable progress on virtually every other indicator we can think of.

Just to mention one - child mortality has been cut in roughly half during this quarter of a century.

There have certainly been wars and conflicts during these decades. But we avoided the end of our civilization in a nuclear Armageddon that we sometimes hovered on the brink of, and overall the number of conflicts and people killed in them started to decline.

I would argue that this was the perhaps best quarter of a century for mankind ever.

For all of its challenges - it was a miraculous period.

And a large part of the explanation certainly lies in the relative stability made possible by the relative order that can be traced back to that misty day off the coast of Newfoundland in 1941.

Trade and economic integration could grow because there was some certainty on the rules that applied, and borders and barriers were gradually reduced. Decolonization gave voice to old nations and new states. The United Nations and its family of organisations and institutions, to quote Dag Hammarskjöld, didn’t bring us to heaven, but at least saved us from hell. In Europe former enemies came together in a unique endeavor of acquiring real sovereignty by sharing formal powers.

And the advantages of open societies and open economies, so evident back then in this divided city and country, eventually brought the Soviet system crashing down.

It was a miraculous period.

But now the mood has clearly shifted.

Not everywhere - but certainly in those countries we can describe as Western democracies. There is talk of the crisis of the global order. There is even talk of a crisis for democracy itself. The mood is somber - sometimes even pessimistic.

And things are indeed changing.

There are three megatrends now affecting us.

The first - geopolitics taking over from globalisation.

The second - the politics of identity taking over from the politics of ideology.

The third - the Industrial Age giving place to the Digital Age.

And together these megatrends are challenging that global order that we have become so dependent upon.

The return of geopolitics is the most obvious of these megatrends.

Here in Europe we have seen the emergence of a revisionist Russia openly and explicitly challenging the golden rule of the global order that borders must never be changed with force.

Most of the borders of our Europe were once upon a time been drawn in blood.

And if you start to opening up the question of borders again, blood is highly likely to flow again.

We saw that during the painful years of the wars of Yugoslav breakup. And since the spring of 2014 more than 10,000 people have been killed in the fighting in the Donbas region.

When we stand firm on the principles in that conflict it is because we have learnt the painful lessons of the past in our part of the world. Borders must never be changed with force.

The return of geopolitics is not only Russian revisionism, but perhaps even more the rise of China, and the profound changes in the global power relationships and global order that this unavoidably brings.

In his large book on China, Henry Kissinger devotes the searching last chapter to trying to answer the question of whether the rise of China will unavoidably lead to a clash and a war with the United States, drawing an uncomfortable parallel with the rise of Germany during the 19th century.

And others, notably the US academic Graham Allison, has reminded us of the famous phrase of Thucydides explaining the outbreak of the Peloponnesian wars two thousand four hundred years ago: “It was the rise of Athens, and the fear that this instilled in Sparta that made war inevitable.”

These concerns are gradually being translated into actual policies. China has set a long term goal for the growth of its defence spending over its goal for overall economic growth, thus setting in on a path to achieve US levels of defence spending within perhaps two decades.

And the new defence doctrine of the United States is very explicit on the changes it sees:

“We are facing increased global disorder, characterised by decline in the longstanding rules-based international order—creating a security environment more complex and volatile than any we have experienced in recent memory. Interstate strategic competition, not terrorism, is now the primary concern in U.S. national security.”

Thus, while the gradual increase in political integration and cooperation was one of the dominant features of the miraculous quarter of a century, in one way facilitated by the dominance of the United States during this period, it is now state rivalry and globally shifting power relationships that dominate the picture.

We are thus no longer moving towards greater stability, but instead towards greater instability.

While the first megatrend is indeed global, the second is particularly pronounced in our Western democracies.

In previous decades I would argue that the political life of our countries was dominated by the politics of ideology and the politics of hope.

There was the belief that a certain set of principles with some form of certainty would bring our societies forward towards ever better conditions and possibilities for all.

Some of this was certainly misguided, or even outright dangerous. But it was still politics driven by hope, and driven by an urge to go forward towards a better future.

The last few decades have seen the decline of the politics of ideology, and the rise of the politics of identity.

And instead of driven by hope, this politics is often driven by fear. Instead of looking forward, it most often looks backwards.

Donald Trump is certainly not the only example of this. We have abundant examples in our own countries.

But when he spoke about “Make America Great Again” he vividly illustrated the change.

Ronald Reagan would never have phrased it like this. He would have said “Make America Great”. Not Again - back towards some fictitious better past, but forward towards an even better future.

But this we now see time after time. Make Russia Great Again. Make China Great Again. Make Islam Great Again.

Looking back towards resurrecting a past that alien forces and foreign influences have in some way deprived us of.

And building on fostering a fear of those alien forces and foreign influences that allegedly risk depriving our societies of their glory and their future.

These, of course, come in different versions.

In many of our countries it’s Islam and other immigrants that are portrayed as the mortal danger.

The Hungarian Prime Minister Victor Orban talks of “the shipwreck of liberal democracy” and says that the EU “wants to dilute the population of Europe and to replace it, to cast aside our culture, our way of life and everything that separates and distinguishes us Europeans.”

He puts nations against nations.

In the present United States it also seems to an open global economy that is the danger.

President Trump in his inaugural address said that “we must protect our borders from the ravages of other countries making our products, stealing our companies and destroying our jobs.”

And there is certainly no shortage of voices in the Islamic world that see the alleged depravity of the West as the mortal danger to their culture and their societies.

Perhaps also President Putin could be added to the list of those preaching a more or less muscular politics of identity. Perhaps his message to us can be summed up as “you have the gays, we have the guns.”

The politics of identity and fear thus seeks to build new barriers where the politics of ideology and hope sought to dismantle or at least reduce their importance. It is the building of walls between nations and cultures, not bridges, that dominates their thinking.

The third megatrend will over time undoubtedly be the most important.

Here in Germany one can often hear talk about the fourth industrial revolution.

I believe this is grossly understates the issue.

I believe we are living in the twilight of the Industrial Age, and the beginning of the Digital Age, and that this over time will have as profound implications for our societies as the centuries of the industrial revolution had.

The smartphone is just over a decade old. Within five years it’s estimated that 90% of the population of the world will be covered by mobile broadband networks with a capacity equal to or better than what we have in most of Europe today.

And that’s when the 5G revolution starts to set in, with vast increases in capacity, when applications of artificial intelligence starts penetrating everywhere and when peace and war in cyberspace becomes perhaps the single most important aspect of international security.

Those living in England in the early part of the 19th century certainly understood that the industrial revolution was going to bring vast changes, but for all that was written no one could predict the magnitude of the changes that would occur.

In the relations between regions, nations and continents. In the social structure of societies with the political changes this was bound to drive. In the ideas and ideologies that were to dominate during the different phases that were to follow.

And the same obviously applies today. IBM didn’t really believe in a big market for computers. Microsoft was rather dismissive of the potential of the internet. Competitors laughed at the first iPhone.

And here we are - with much to come.

The digital revolution brings enormous promise in very many respects, not least combined with other advances in science and technology. We can detect and combat diseases in ways previously unthinkable. We can crack the codes of the remaining mysteries of our times.

But the dangers are also there.

We see China forging ahead with a determination there is hardly any equal to in our societies.

With no privacy rules whatsoever, and thus access to enormous amounts of data, there is a risk that cannot be neglected that it will dominate the race into artificial intelligence, with vast consequences in practically every respect.

And there is little doubt that the regime in Beijing will use these technologies also in seeking to build its own 2084 - George Orwell might have been wrong on the timing, but not on the substance.

To these three megatrends could certainly be added others. Scientists are telling us that we have entered the age of the anthroposcene, when the activities and actions of humans changes the very nature of our Earth, with climate change as the most obvious example.

What is truly worrying is that in the midst of these changes and challenges, we see a questioning of the very concept of a global order.

That that which we refer to as the global order needs to be revisited in light of these and other changes is without doubt. But while I would argue that we need even more of a robust global order, there are now those arguing that what we need is less of an order and de facto more of disorder.

President Putin, in a speech to the Valdai Club a couple of years ago, said that we are living in a time when he certainly doesn’t accept the old rules, and that the question is whether we should change these rules or have no rules at all for the relations between states and nations.

And he rather ominously added that periods of change in the global order are normally associated with series of wars.

In the other direction, the new national security strategy of the United States for the first time avoids any mention of an international or global order. To the contrary, it says that previous policies of engagement and inclusion were based on a premise that mostly was false.

Instead, it portrays a world of “strong, sovereign and independent nations” in fierce competition with each other. It says that “a central continuity in history is the contest for power”, and says that the US “will compete with all tools of national power.”

Words like “international order” or “global community” are totally absent. This might sound innocent to American ears, where concepts of sharing sovereignty have never been fully anchored, and is most certainly sounding attractive to a Kremlin thinking in similar terms, but sounds outright alarming to most Europeans.

Based on our historical experience, a situation in which sovereign states fiercely competes with each other in all domains without any agreed framework or rules, for us sounds like an almost certain recipe for confrontation and conflict, indeed, sooner or later, for war itself.

That is certainly not the intention of those who authored this strategy. They simply aim for an America without constraints to win. Against everyone. Everywhere. Every time.

There is no doubt that the United States is still the world’s most powerful country. But neither is there any doubt that power is gradually shifting, and that the relative power of the United States, and indeed of the combined West, is slowly but certainly declining.

Thus, a strategy based on just competition, seeking to win everywhere, every time against everyone, is up against the lesson of history that it will simply not work.

Add to this that we are increasingly faced with challenges where the possible solutions lie beyond the possibilities of even the largest sovereign states.

We would all be affected by chaos in outer space as well as cyberspace. Migration simply can’t be handled just by trying to build walls. Climate change and cross-environmental issues can’t be ignored. The breakdown of order in sensitive regions creates waves of disorder, and sometimes even violence, stretching into our own societies. No one can guarantee that we will never face a serious global pandemic.

And I could go on. We need a global order. Now more than ever.

The European Union is and will forever remain a work in progress. Whether it will produce that “ever closer union” once dreamt of remains to be seen. But while the Europe of dreams might have faded recently, the Europe of necessity is clearly on the rise.

Time after time, when new issues arise, we see the leaders of Europe rushing to Brussels for another summit meeting, knowing that on their own they will achieve little, but together they might achieve something, and over time perhaps even a solution.

And the record certainly speaks in their favour.

War in our part of Europe certainly looks very distant. Our economies are intertwined to a depth the British are now painfully finding out. The Eurocrisis certainly produced a fair share of not entirely successful summits, but the sum of them took us out of the crisis and back to growth. The refugee crisis of 2015 wasn’t foreseen, solutions are still being discussed, but gradually new structures are being created. And sanctions against Russia, supporting the principle that borders must never be changed with force, are still in place.

The record is, at closer inspection, rather impressive.

These and others issues have during the last decade or so forced the European Union to look primarily inwards, and to some extent that is still the case.

But I would argue that it will now be increasingly necessary for the EU to look outward, to see the trends in the world, the dangers to global order and the urgent necessity to defend the principles of a global order and be an active partner in shaping such an order for the future.

It’s a tall order.

It entails - and this is almost painful to say - standing up also to the United States. Certainly not in every respect, and hopefully without endangering the fundamental links across the Atlantic, but certainly on issues where our rights are violated.

Just one example: when the US sees sanctions against European companies as its number one instrument against Iran, it is not primarily violating our economic interests, but our sovereignty in foreign affairs. We are deprived of the right to pursue our own foreign policy. This is utterly unacceptable.

It entails reaching out to the rest of the world. To a democratic India that will soon be the world’s most populous country. To a Japan we share many values and principles. To Latin America and Africa and to all others.

A Europe that not only protects its interests. That’s obviously important.

But a Europe that also projects its values and principles. That must not be seen as less important.

Henry Kissinger devoted his latest book to the very issue of global order.

“Our age”, he wrote, “is insistently, at times almost desperately, in pursuit of a concept of global order. Chaos threatens side by side with unprecedented interdependence.”

“Are we”, he asked, “facing a period in which beyond the restraints of any order determine the future?”

He doesn’t answer the question.

It’s up to you now leaving your studies, and entering the affairs of the world, to find it.

Thank you.