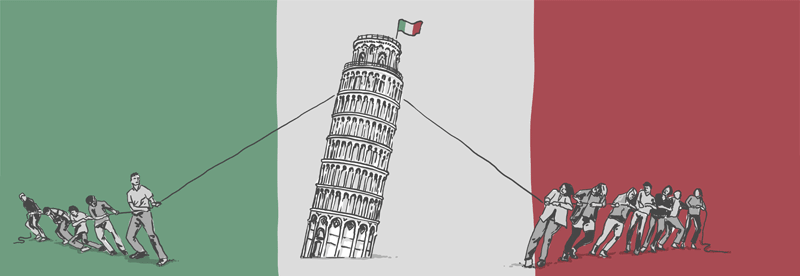

Hertie School experts react after voters reject constitutional reforms.

“Given the political results we have witnessed in 2016 so far, it is tempting to record this vote as yet another victory for anti-EU populists against establishment parties. It is true that the architects of this defeat were Beppe Grillo’s Movimento 5 Stelle. This was also, though, a reform opposed by the like of Mario Monti, the former PM and a pillar of reformist Europeanism. Those who opposed Mr. Renzi did so not because they were against his reformist project per se but because they saw this change – by cementing one-party dominance and strengthening Italy’s regions – as worsening rather than addressing the challenges of nepotism and inefficiency plaguing Italian governance. As with other recent referendums, the vote was used as an opportunity to clip the wings of a dominant party and leadership seen to over-promise yet under-deliver.

Mr. Renzi has suffered a huge setback but it is certainly too early, given his historic hold over the centre-left, to write him off entirely. It would also be foolish to lump together Mr. Grillo’s movement – against the current trajectory of the EU without being against integration per se – with the Marine Le Pen’s of this world. Like the prospect of Podemos’ entry into government earlier this year, the rise of the 5-star movement certainly challenges the EU but in a manner EU leaders ought to take seriously, rather than dismiss as a lurch back to nationalist protectionism. The irony of the result is that, by maintaining the present legislative framework, the ‘No’ result would make it nigh impossible for a future coalition of euro-sceptic parties to seriously challenge Italy’s place in the EU and Euro projects. Europe’s opinion formers should not allow this result to go down in history as a victory for right-wing populism.” – Mark Dawson, Professor of European Law and Governance at the Hertie School

“As in the case of the Brexit referendum, the Italian constitutional reform vote showed that referenda can create more problems than they solve. Their first problem is that they pose only one simple question but receive answers to many complex questions. Matteo Renzi is not the first to discover that a referendum on a complex substantive question turns out to be a popularity contest of the prime minister and mobilizes many actors for reasons that have little or nothing to do with the issue at stake. Second, referenda are good in taking political decisions or preventing them but not in shaping them. The Brexit vote leaves the British political system in a mess, and the Italian No does not solve the well-known problems of the Italian political system but simply maintains the status quo. What is worse, its clear outcome may prevent political solutions in the near future. Third, referenda are not well suited for divided societies because simple yes/no logic creates clear winners and losers instead of allowing for compromises between different camps. This is not what Italy needs.

The referendum should not be talked into a crisis of Europe. At stake was a reform of the Italian political system. Europe does however get a problem if it becomes synonymous with efficient rule from the top. If some political actors can mobilize in the name of safeguarding national democracy and self-determination against European austerity policies and German dominance, they are likely to win. There-is-no-alternative is not a good argument for Europe but a bad one which creates resistance. What is going to happen to Italy remains to be seen. The referendum was a missed chance, but Italy has learned to live with short lived governments and many veto players for many decades.” – Markus Jachtenfuchs, Professor of European and Global Governance at the Hertie School

“What the literature on referendum voting suggests is that voters take cues – from parties or interest groups – to reach their decision on sometimes complex and technical matters which the Italian referendum certainly posed. Given the unpopularity of Renzi’s government, the cue that most voters took was to vote ‘No’, just as seems to have happened in the UK and, more recently, Colombia. This does not necessarily provide an argument against direct democracy – particularly the citizen-initiated kind – but against political leaders outsourcing their political conflicts to the people.” – Arndt Leininger, PhD candidate at the Hertie School

“Following a clear defeat in the Constitutional referendum, Renzi decided to resign as Italy’s Prime Minister. This opens a scenario of prolonged political instability. The President of the Republic – Sergio Mattarella – is unlikely to dissolve Parliament and will rather explore the possibility of forming a technocratic government with the aim of reforming the electoral law – which is currently designed for only one chamber: the Senate was supposed to be turned into a consultative unelected body under the Constitutional reform. In order to halt the rising tide of the populist 5 star movement, Renzi’s Democratic Party and Berlusconi’s right-wing party are likely to come to an agreement around a new proportional electoral law. This will force coalition governments going forward, hence undermining governability also over the longer term. As such, Italy is expected to be stuck in a political quagmire, making any further much needed reforms (starting from the fragile banking system) very unlikely.” – Alessio Terzi, PhD candidate at the Hertie School

More about the experts

-

Mark Dawson, Professor of European Law and Governance

-

Markus Jachtenfuchs, Professor of European and Global Governance